The Winnebago County Local Emergency Planning Committee holds an annual conference on disaster preparedness. Normally, the group focuses on hazardous materials. This year, the issue of mass shootings was added to the agenda. In this week’s Friday Forum, WNIJ’s Chase Cavanaugh highlights two speakers who talk about responding to these incidents.

In recent mass shootings, it’s common to see a wide variety of groups on site. There may be police investigating crime scenes and apprehending suspects, medical teams treating the wounded, and counselors trying to help survivors deal with the mental health trauma they endured.

But one speaker at the Rockford conference in mid-April said these groups don’t always work together so well.

G. B. Jones is a special agent with the Milwaukee branch of the FBI. He says local law enforcement often was forced to shoulder the burden of security and investigation, with higher-level authorities constrained by their jurisdictions. Jones says this was particularly true in the wake of the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting.

“At that time, the FBI did not have any jurisdiction or responsibility to respond to a mass shooting, because it’s a homicide," he said. "That’s a local crime. That’s not a federal crime unless it occurs to a federal agent or federal employee in the commission of their duties or on federal property.”

The FBI was similarly constrained when the Northern Illinois University police department asked for help responding to its 2008 campus shooting. So Agent Jones found a way to work around the jurisdictional limits.

“Of all of the weapons that we were going to find, the likelihood that any of those weapons were manufactured in the state of Illinois was pretty small,” he said. "So that was my hook: I called this a firearms violation, and I had everyone in the FBI going down there to work on this caper."

Even when Jones arrived on the scene, he needed to work with an NIU police chief who didn’t want the Illinois State Police to be involved. So, when Jones needed ISP’s help with crime scene investigation, he “looped them in.”

“‘The FBI doesn’t routinely do homicide scenes, so I need your homicide team to come help with the FBI as we do this evidence collection. So you’re working for the FBI on this one, but this is a collective effort,’” Jones told the state police. "See what I did there? I’m going to the guys that are going to get the work done, because we are able to develop this through a relationship."

Campus police, on the other hand, were able to do what they do best.

“The NIU police department, almost every one of their officers was an emergency medical technician. Not just a first responder, but an EMT, and that saved lives that day,” Jones said.

In addition to campus and state police, Jones says the FBI was assisted by other federal agencies and some of the bureau’s more specialized divisions.

“I dare say that, even now, we probably know more about the NIU shooter than any other shooter that has happened either before or since, because we had our behavioral analysis guys on the ground within a day of the shooting," he said. "They were actually able to do real-time interviews with family and friends and relatives of the shooter, so that we could maybe understand his motivations a little bit better."

This was especially important because the shooter had committed suicide after the attack. Jones says the NIU shooting was the major catalyst for having the FBI take a more active role in responding to mass shootings.

With the passage of the Investigative Assistance for Violent Crimes Act in 2012, and an accompanying Homeland Security Directive, the bureau could intervene legally under the authority of counterterrorism and counterintelligence. Jones adds that FBI assistance in more recent shootings means local authorities also have access to a lot of specialists.

“Special agent bomb technicians, evidence response teams, crisis management coordinators. They’re the ones that set up the command post and make order out of chaos," he said. "SWAT Teams, NCAVC is the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime. They’re the behavioral profilers. Media assistance and our office of victim assistance, all those go out the door immediately.”

Jones says this coordinated response is essential in any mass shooting incident. However, his focus is on the immediate incident and aftermath.

Suzanne Bernier, another speaker at the April conference, is a crisis-management consultant who helps companies and organizations make plans for disasters and emergencies like mass shootings. She says it’s important not only for organizations to be prepared but also to be flexible with the circumstances.

“It’s really important to have a plan in place, trained staff in place, awareness overall of the kinds of risks and threats people may face and how they should deal with it, but also just as important to recognize that all the plans in the world sometimes are not going to be able to help a situation," she said. "You’re going to have to get creative.”

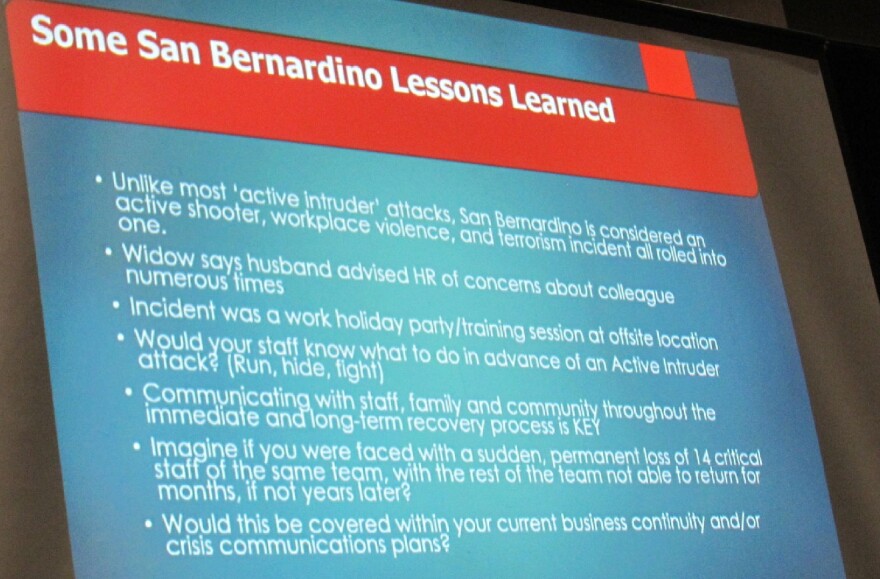

Bernier says there was a distinct lack of flexibility in the response to the 2015 San Bernardino shooting. The public health department previously had held unannounced active shooter drills, so when San Bernardino Public Health employees saw the shooters, some thought it was just another drill.

“I’m not just talking about active-shooter incidents, but any type of an emergency situation," she said. "One of the common challenges and failures is that the balance between making sure that you’re getting information out as quickly as possible, but that it’s the accurate and correct information.”

If there had been less ambiguity about shooter drills, Bernier says some people might have been able to react quicker and hide from the shooter. This may have reduced casualties. Even after the shooting, Bernier says resources appeared to be prioritized only for those who were wounded physically.

“There are a lot of people who might not have physically been injured, might not have lost their home, but still are mentally impacted,” she said.

This came to a head when human resources told the shooting survivors that they all had to return to work the following Monday. Many staff members said they didn’t feel it was safe enough to return, or they were mentally triggered by simply being at their workplace.

Employee outcry led to HR rescinding the immediate return order, but it led to at least one employee quitting and others losing trust in their managers. Bernier says some of this was due to strict business-continuity plans and HR regulations. She advises other organizations to apply their emergency plans to scenarios like San Bernardino and see how they can cope with permanent staff losses.

“They should be taking a look at reviewing and seeing if, with the plans they have now, they would adequately be able to help a community respond and recover from an active intruder-type incident," she said. "In a lot of cases, probably not.”

Fortunately, the survivors of San Bernardino were able to find support from living victims of other mass shootings, including those from the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. Bernier says the club manager was particularly effective in reaching out.

“He is now starting his own nonprofit that is going to help and train survivors of terror and active-intruder incidents on the things that they wish they could have been trained in, that might have helped them save or prevent lives from being lost as well -- a great initiative that’s also connecting survivors from all across America.”

Ultimately, both Agent G.B. Jones and Suzanne Bernier hope that enough planning and foresight can prevent future mass shootings. But, when another shooting does occur, they aim to ensure a comprehensive response in the face of disaster and proper long-term support for those who survive.